What Distinguishes Adbusters From Earlier Movements Like Pop Art and Fluxus?

Pop art is an art motility that emerged in the United kingdom and the United states of america during the mid- to late-1950s.[1] [ii] The motility presented a challenge to traditions of fine fine art by including imagery from popular and mass culture, such as advertizing, comic books and mundane mass-produced objects. One of its aims is to use images of popular (as opposed to elitist) culture in art, emphasizing the banal or kitschy elements of any civilisation, nearly often through the use of irony.[iii] It is also associated with the artists' utilize of mechanical means of reproduction or rendering techniques. In pop fine art, material is sometimes visually removed from its known context, isolated, or combined with unrelated material.[2] [3]

Among the early artists that shaped the popular art movement were Eduardo Paolozzi and Richard Hamilton in Great britain, and Larry Rivers, Ray Johnson. Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns among others in the Us. Pop art is widely interpreted every bit a reaction to the then-dominant ideas of abstract expressionism, likewise every bit an expansion of those ideas.[4] Due to its utilization of found objects and images, information technology is like to Dada. Pop fine art and minimalism are considered to be art movements that precede postmodern art, or are some of the earliest examples of postmodern art themselves.[5]

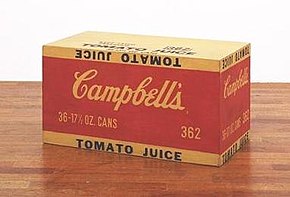

Popular art often takes imagery that is currently in use in advertising. Product labeling and logos figure prominently in the imagery chosen by popular artists, seen in the labels of Campbell'due south Soup Cans, by Andy Warhol. Even the labeling on the exterior of a aircraft box containing nutrient items for retail has been used equally subject matter in popular fine art, as demonstrated by Warhol's Campbell'due south Tomato Juice Box, 1964 (pictured).

Origins [edit]

The origins of pop art in North America developed differently from Uk.[3] In the United States, popular art was a response by artists; it marked a return to hard-edged limerick and representational fine art. They used impersonal, mundane reality, irony, and parody to "defuse" the personal symbolism and "painterly looseness" of abstract expressionism.[iv] [6] In the U.Due south., some artwork by Larry Rivers, Alex Katz and Man Ray anticipated pop fine art.[7]

By dissimilarity, the origins of pop fine art in post-State of war Britain, while employing irony and parody, were more academic. Britain focused on the dynamic and paradoxical imagery of American popular civilization as powerful, manipulative symbolic devices that were affecting whole patterns of life, while simultaneously improving the prosperity of a society.[6] Early pop art in United kingdom was a affair of ideas fueled by American popular civilisation when viewed from distant.[iv] Similarly, pop fine art was both an extension and a repudiation of Dadaism.[4] While popular art and Dadaism explored some of the same subjects, pop fine art replaced the subversive, satirical, and anarchic impulses of the Dada movement with a detached affirmation of the artifacts of mass culture.[4] Amidst those artists in Europe seen as producing piece of work leading up to pop art are: Pablo Picasso, Marcel Duchamp, and Kurt Schwitters.

Proto-popular [edit]

Although both British and American pop art began during the 1950s, Marcel Duchamp and others in Europe like Francis Picabia and Man Ray predate the movement; in addition in that location were some earlier American proto-pop origins which utilized "as found" cultural objects.[4] During the 1920s, American artists Patrick Henry Bruce, Gerald Irish potato, Charles Demuth and Stuart Davis created paintings that contained pop civilisation imagery (mundane objects culled from American commercial products and advertising blueprint), almost "prefiguring" the popular fine art movement.[8] [9]

United Kingdom: the Independent Group [edit]

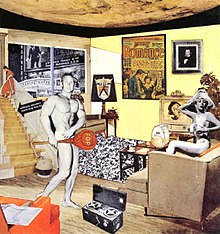

The Independent Group (IG), founded in London in 1952, is regarded as the precursor to the pop art movement.[2] [x] They were a gathering of young painters, sculptors, architects, writers and critics who were challenging prevailing modernist approaches to culture too as traditional views of fine fine art. Their group discussions centered on popular culture implications from elements such as mass advertisement, movies, product design, comic strips, science fiction and engineering. At the start Independent Group meeting in 1952, co-founding member, artist and sculptor Eduardo Paolozzi presented a lecture using a series of collages titled Bunk! that he had assembled during his time in Paris between 1947 and 1949.[2] [ten] This textile of "found objects" such as advertising, comic book characters, magazine covers and diverse mass-produced graphics by and large represented American popular culture. One of the collages in that presentation was Paolozzi'due south I was a Rich Man's Plaything (1947), which includes the start apply of the discussion "popular", appearing in a cloud of smoke emerging from a revolver.[2] [eleven] Following Paolozzi's seminal presentation in 1952, the IG focused primarily on the imagery of American popular culture, specially mass advertising.[6]

Co-ordinate to the son of John McHale, the term "pop fine art" was first coined by his father in 1954 in conversation with Frank Cordell,[12] although other sources credit its origin to British critic Lawrence Alloway.[13] [14] (Both versions agree that the term was used in Independent Group discussions by mid-1955.)

"Pop fine art" every bit a moniker was then used in discussions past IG members in the Second Session of the IG in 1955, and the specific term "pop art" beginning appeared in published print in the article "But Today We Collect Ads" by IG members Alison and Peter Smithson in Ark mag in 1956.[15] However, the term is oft credited to British fine art critic/curator Lawrence Alloway for his 1958 essay titled The Arts and the Mass Media, even though the precise language he uses is "popular mass culture".[16] "Furthermore, what I meant by it then is not what it means now. I used the term, and as well 'Pop Culture' to refer to the products of the mass media, not to works of art that describe upon popular culture. In any example, sometime between the winter of 1954–55 and 1957 the phrase acquired currency in chat..."[17] Nevertheless, Alloway was i of the leading critics to defend the inclusion of the imagery of mass civilization in the fine arts. Alloway antiseptic these terms in 1966, at which time Popular Art had already transited from art schools and small galleries to a major forcefulness in the artworld. But its success had non been in England. Practically simultaneously, and independently, New York City had get the hotbed for Popular Art.[17]

In London, the annual Royal Order of British Artists (RBA) exhibition of young talent in 1960 showtime showed American pop influences. In January 1961, the virtually famous RBA-Young Contemporaries of all put David Hockney, the American R B Kitaj, New Zealander Baton Apple tree, Allen Jones, Derek Boshier, Joe Tilson, Patrick Caulfield, Peter Phillips, Pauline Boty and Peter Blake on the map; Apple designed the posters and invitations for both the 1961 and 1962 Immature Contemporaries exhibitions.[18] Hockney, Kitaj and Blake went on to win prizes at the John-Moores-Exhibition in Liverpool in the same year. Apple tree and Hockney traveled together to New York during the Majestic College'due south 1961 summer break, which is when Apple starting time fabricated contact with Andy Warhol – both later moved to the United States and Apple tree became involved with the New York popular art scene.[18]

U.s. [edit]

Although pop art began in the early 1950s, in America it was given its greatest impetus during the 1960s. The term "popular art" was officially introduced in Dec 1962; the occasion was a "Symposium on Pop Art" organized by the Museum of Modern Art.[19] Past this fourth dimension, American advertising had adopted many elements of modern art and functioned at a very sophisticated level. Consequently, American artists had to search deeper for dramatic styles that would distance art from the well-designed and clever commercial materials.[6] As the British viewed American popular culture imagery from a somewhat removed perspective, their views were often instilled with romantic, sentimental and humorous overtones. By contrast, American artists, bombarded every solar day with the diversity of mass-produced imagery, produced work that was generally more than bold and ambitious.[x]

According to historian, curator and critic Henry Geldzahler, "Ray Johnson's collages Elvis Presley No. 1 and James Dean stand as the Plymouth Rock of the Pop movement."[20] Author Lucy Lippard wrote that "The Elvis ... and Marilyn Monroe [collages] ... heralded Warholian Pop."[21] Johnson worked as a graphic designer, met Andy Warhol by 1956 and both designed several volume covers for New Directions and other publishers. Johnson began mailing out whimsical flyers advertising his design services printed via offset lithography. He later became known as the father of mail fine art equally the founder of his "New York Correspondence School," working minor past stuffing clippings and drawings into envelopes rather than working larger similar his contemporaries.[22] A note about the comprehend image in January 1958's Art News pointed out that "[Jasper] Johns' first i-man prove ... places him with such ameliorate-known colleagues equally Rauschenberg, Twombly, Kaprow and Ray Johnson".[23]

Indeed, two other important artists in the institution of America'southward pop art vocabulary were the painters Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg.[10] Rauschenberg, who like Ray Johnson attended Black Mount Higher in Due north Carolina later on Earth War II, was influenced by the earlier work of Kurt Schwitters and other Dada artists, and his belief that "painting relates to both fine art and life" challenged the dominant modernist perspective of his time.[24] His apply of discarded readymade objects (in his Combines) and popular civilization imagery (in his silkscreen paintings) connected his works to topical events in everyday America.[10] [25] [26] The silkscreen paintings of 1962–64 combined expressive brushwork with silkscreened magazine clippings from Life, Newsweek, and National Geographic. Johns' paintings of flags, targets, numbers, and maps of the U.South. too iii-dimensional depictions of ale cans drew attention to questions of representation in art.[27] Johns' and Rauschenberg's work of the 1950s is frequently referred to as Neo-Dada, and is visually distinct from the prototypical American popular art which exploded in the early on 1960s.[28] [29]

Roy Lichtenstein is of equal importance to American popular art. His work, and its use of parody, probably defines the basic premise of popular art better than any other.[ten] Selecting the old-fashioned comic strip as subject field affair, Lichtenstein produces a hard-edged, precise composition that documents while also parodying in a soft manner. Lichtenstein used oil and Magna paint in his best known works, such as Drowning Daughter (1963), which was appropriated from the lead story in DC Comics' Cloak-and-dagger Hearts #83. (Drowning Daughter is part of the collection of the Museum of Modern Fine art.)[xxx] His work features thick outlines, bold colors and Ben-Day dots to represent sure colors, equally if created by photographic reproduction. Lichtenstein said, "[abstract expressionists] put things downward on the canvas and responded to what they had done, to the colour positions and sizes. My mode looks completely different, but the nature of putting downward lines pretty much is the aforementioned; mine just don't come up out looking calligraphic, like Pollock's or Kline's."[31] Popular fine art merges pop and mass culture with fine art while injecting humor, irony, and recognizable imagery/content into the mix.

The paintings of Lichtenstein, like those of Andy Warhol, Tom Wesselmann and others, share a direct attachment to the commonplace paradigm of American popular civilization, just likewise treat the subject in an impersonal manner conspicuously illustrating the idealization of mass production.[10]

Andy Warhol is probably the most famous figure in pop fine art. In fact, art critic Arthur Danto in one case chosen Warhol "the nearest thing to a philosophical genius the history of art has produced".[19] Warhol attempted to take popular beyond an artistic style to a life style, and his work often displays a lack of homo arrayal that dispenses with the irony and parody of many of his peers.[32] [33]

Early on U.S. exhibitions [edit]

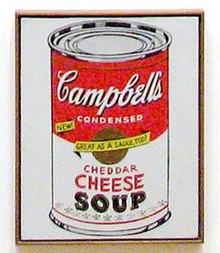

The Cheddar Cheese canvass from Andy Warhol'south Campbell's Soup Cans, 1962.

Claes Oldenburg, Jim Dine and Tom Wesselmann had their showtime shows in the Judson Gallery in 1959 and 1960 and afterward in 1960 through 1964 along with James Rosenquist, George Segal and others at the Greenish Gallery on 57th Street in Manhattan. In 1960, Martha Jackson showed installations and assemblages, New Media – New Forms featured Hans Arp, Kurt Schwitters, Jasper Johns, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg, Jim Dine and May Wilson. 1961 was the year of Martha Jackson's spring show, Environments, Situations, Spaces.[34] [35] Andy Warhol held his first solo exhibition in Los Angeles in July 1962 at Irving Blum'due south Ferus Gallery, where he showed 32 paintings of Campell's soup cans, one for every flavor. Warhol sold the set of paintings to Blum for $i,000; in 1996, when the Museum of Modernistic Fine art caused it, the ready was valued at $fifteen million.[19]

Donald Factor, the son of Max Gene Jr., and an art collector and co-editor of avant-garde literary mag Nomad, wrote an essay in the mag's terminal issue, Nomad/New York. The essay was one of the first on what would get known as pop art, though Factor did non use the term. The essay, "4 Artists", focused on Roy Lichtenstein, James Rosenquist, Jim Dine, and Claes Oldenburg.[36]

In the 1960s, Oldenburg, who became associated with the popular fine art motility, created many happenings, which were performance art-related productions of that time. The name he gave to his own productions was "Ray Gun Theater". The cast of colleagues in his performances included: artists Lucas Samaras, Tom Wesselmann, Carolee Schneemann, Öyvind Fahlström and Richard Artschwager; dealer Annina Nosei; fine art critic Barbara Rose; and screenwriter Rudy Wurlitzer.[37] His first wife, Patty Mucha, who sewed many of his early on soft sculptures, was a abiding performer in his happenings. This advised, oft humorous, approach to art was at bully odds with the prevailing sensibility that, by its nature, art dealt with "profound" expressions or ideas. In December 1961, he rented a store on Manhattan'southward Lower East Side to business firm The Store, a month-long installation he had showtime presented at the Martha Jackson Gallery in New York, stocked with sculptures roughly in the form of consumer appurtenances.[37]

Opening in 1962, Willem de Kooning'southward New York art dealer, the Sidney Janis Gallery, organized the groundbreaking International Exhibition of the New Realists, a survey of new-to-the-scene American, French, Swiss, Italian New Realism, and British pop art. The fifty-four artists shown included Richard Lindner, Wayne Thiebaud, Roy Lichtenstein (and his painting Blam), Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, James Rosenquist, Jim Dine, Robert Indiana, Tom Wesselmann, George Segal, Peter Phillips, Peter Blake (The Love Wall from 1961), Öyvind Fahlström, Yves Klein, Arman, Daniel Spoerri, Christo and Mimmo Rotella. The show was seen by Europeans Martial Raysse, Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely in New York, who were stunned by the size and look of the American artwork. Also shown were Marisol, Mario Schifano, Enrico Baj and Öyvind Fahlström. Janis lost some of his abstract expressionist artists when Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell, Adolph Gottlieb and Philip Guston quit the gallery, but gained Dine, Oldenburg, Segal and Wesselmann.[38] At an opening-night soiree thrown by collector Burton Tremaine, Willem de Kooning appeared and was turned away past Tremaine, who ironically endemic a number of de Kooning'south works. Rosenquist recalled: "at that moment I thought, something in the fine art earth has definitely changed".[19] Turning abroad a respected abstract artist proved that, as early as 1962, the pop art movement had begun to dominate art culture in New York.

A scrap before, on the W Coast, Roy Lichtenstein, Jim Dine and Andy Warhol from New York Metropolis; Phillip Hefferton and Robert Dowd from Detroit; Edward Ruscha and Joe Goode from Oklahoma Urban center; and Wayne Thiebaud from California were included in the New Painting of Common Objects evidence. This first popular fine art museum exhibition in America was curated by Walter Hopps at the Pasadena Art Museum.[39] Pop art was ready to change the art globe. New York followed Pasadena in 1963, when the Guggenheim Museum exhibited Six Painters and the Object, curated by Lawrence Alloway. The artists were Jim Dine, Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg, James Rosenquist, and Andy Warhol.[40] Another pivotal early exhibition was The American Supermarket organised past the Bianchini Gallery in 1964. The show was presented every bit a typical small supermarket environment, except that everything in information technology—the produce, canned goods, meat, posters on the wall, etc.—was created by prominent pop artists of the time, including Apple, Warhol, Lichtenstein, Wesselmann, Oldenburg, and Johns. This projection was recreated in 2002 as part of the Tate Gallery's Shopping: A Century of Art and Consumer Culture.[41]

Past 1962, pop artists started exhibiting in commercial galleries in New York and Los Angeles; for some, it was their beginning commercial one-man show. The Ferus Gallery presented Andy Warhol in Los Angeles (and Ed Ruscha in 1963). In New York, the Greenish Gallery showed Rosenquist, Segal, Oldenburg, and Wesselmann. The Stable Gallery showed R. Indiana and Warhol (in his showtime New York prove). The Leo Castelli Gallery presented Rauschenberg, Johns, and Lichtenstein. Martha Jackson showed Jim Dine and Allen Stone showed Wayne Thiebaud. By 1966, subsequently the Green Gallery and the Ferus Gallery closed, the Leo Castelli Gallery represented Rosenquist, Warhol, Rauschenberg, Johns, Lichtenstein and Ruscha. The Sidney Janis Gallery represented Oldenburg, Segal, Dine, Wesselmann and Marisol, while Allen Stone continued to represent Thiebaud, and Martha Jackson connected representing Robert Indiana.[42]

In 1968, the São Paulo nine Exhibition – Surround U.S.A.: 1957–1967 featured the "Who'south Who" of pop fine art. Considered every bit a summation of the classical stage of the American pop fine art menstruum, the exhibit was curated by William Seitz. The artists were Edward Hopper, James Gill, Robert Indiana, Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol and Tom Wesselmann.[43]

France [edit]

Nouveau réalisme refers to an artistic movement founded in 1960 past the art critic Pierre Restany[44] and the creative person Yves Klein during the showtime collective exposition in the Apollinaire gallery in Milan. Pierre Restany wrote the original manifesto for the grouping, titled the "Constitutive Announcement of New Realism," in Apr 1960, proclaiming, "Nouveau Réalisme—new ways of perceiving the real."[45] This joint declaration was signed on 27 October 1960, in Yves Klein's workshop, past 9 people: Yves Klein, Arman, Martial Raysse, Pierre Restany, Daniel Spoerri, Jean Tinguely and the Ultra-Lettrists, Francois Dufrêne, Raymond Hains, Jacques de la Villeglé; in 1961 these were joined by César, Mimmo Rotella, then Niki de Saint Phalle and Gérard Deschamps. The artist Christo showed with the group. It was dissolved in 1970.[45]

Contemporary of American Pop Art—often conceived equally its transposition in French republic—new realism was along with Fluxus and other groups one of the numerous tendencies of the avant-garde in the 1960s. The group initially chose Overnice, on the French Riviera, equally its home base since Klein and Arman both originated at that place; new realism is thus ofttimes retrospectively considered past historians to be an early representative of the École de Nice movement.[46] In spite of the diversity of their plastic linguistic communication, they perceived a common footing for their work; this being a method of direct cribbing of reality, equivalent, in the terms used by Restany; to a "poetic recycling of urban, industrial and ad reality".[47]

Spain [edit]

In Spain, the study of pop art is associated with the "new figurative", which arose from the roots of the crisis of informalism. Eduardo Approach could be said to fit within the pop fine art trend, on account of his interest in the environs, his critique of our media civilization which incorporates icons of both mass media advice and the history of painting, and his scorn for nearly all established artistic styles. However, the Spanish artist who could be considered almost authentically part of "pop" art is Alfredo Alcaín, because of the employ he makes of popular images and empty spaces in his compositions.

Also in the category of Spanish pop fine art is the "Chronicle Squad" (El Equipo Crónica), which existed in Valencia between 1964 and 1981, formed past the artists Manolo Valdés and Rafael Solbes. Their movement can exist characterized as "pop" because of its apply of comics and publicity images and its simplification of images and photographic compositions. Filmmaker Pedro Almodóvar emerged from Madrid'due south "La Movida" subculture of the 1970s making depression upkeep super eight pop art movies, and he was afterwards called the Andy Warhol of Kingdom of spain by the media at the fourth dimension. In the book Almodovar on Almodovar, he is quoted equally saying that the 1950s film "Funny Face" was a primal inspiration for his work. One pop trademark in Almodovar'due south films is that he always produces a imitation commercial to exist inserted into a scene.

New Zealand [edit]

In New Zealand, pop art has predominately flourished since the 1990s, and is often connected to Kiwiana. Kiwiana is a pop-centered, idealised representation of classically Kiwi icons, such as meat pies, kiwifruit, tractors, jandals, Four Square supermarkets; the inherent campness of this is frequently subverted to signify cultural messages.[48] Dick Frizzell is a famous New Zealand pop creative person, known for using older Kiwiana symbols in ways that parody modern culture. For example, Frizzell enjoys imitating the work of foreign artists, giving their works a unique New Zealand view or influence. This is done to show New Zealand'south historically subdued affect on the world; naive art is continued to Aotearoan pop fine art this way.[49]

This tin can be too done in an abrasive and deadpan fashion, as with Michel Tuffrey'southward famous work Pisupo Lua Afe (Corned Beefiness 2000). Of Samoan ancestry, Tuffery constructed the work, which represents a bull, out of processed food cans known equally pisupo. It is a unique work of western pop art because Tuffrey includes themes of neocolonialism and racism against non-western cultures (signified by the food cans the work is fabricated of, which represent economic dependence brought on Samoans by the west). The undeniable indigenous viewpoint makes information technology stand out against more than mutual non-indigenous works of pop art.[l] [51]

One of New Zealand's primeval and famous pop artists is Billy Apple, one of the few non-British members of the Royal Society of British Artists. Featured among the likes of David Hockney, American R.B. Kitaj and Peter Blake in the January 1961 RBA exhibition Young Contemporaries, Apple tree quickly became an iconic international creative person of the 1960s. This was before he conceived his moniker of 'Billy Apple", and his work was displayed under his birth proper noun of Barrie Bates. He sought to distinguish himself by advent too as proper noun, so bleached his hair and eyebrows with Lady Clairol Instant Creme Whip. Later, Apple was associated with the 1970s Conceptual Art movement. [52]

Japan [edit]

In Japan, pop art evolved from the nation'southward prominent avant-garde scene. The employ of images of the mod globe, copied from magazines in the photomontage-style paintings produced by Harue Koga in the late 1920s and early 1930s, foreshadowed elements of popular fine art.[53] The Japanese Gutai movement led to a 1958 Gutai exhibition at Martha Jackson's New York gallery that preceded past two years her famous New Forms New Media show that put Pop Art on the map.[54] The piece of work of Yayoi Kusama contributed to the development of pop art and influenced many other artists, including Andy Warhol.[55] [56] In the mid-1960s, graphic designer Tadanori Yokoo became one of the well-nigh successful pop artists and an international symbol for Japanese popular fine art. He is well known for his advertisements and creating artwork for pop civilization icons such every bit commissions from The Beatles, Marilyn Monroe, and Elizabeth Taylor, among others.[57] Another leading popular artist at that time was Keiichi Tanaami. Iconic characters from Japanese manga and anime have also become symbols for pop art, such as Speed Racer and Astro Boy. Japanese manga and anime also influenced later pop artists such as Takashi Murakami and his superflat movement.

Italy [edit]

In Italy, by 1964, pop art was known and took unlike forms, such as the "Scuola di Piazza del Popolo" in Rome, with popular artists such as Mario Schifano, Franco Angeli, Giosetta Fioroni, Tano Festa, Claudio Cintoli, and some artworks past Piero Manzoni, Lucio Del Pezzo, Mimmo Rotella and Valerio Adami.

Italian pop art originated in 1950s culture – the works of the artists Enrico Baj and Mimmo Rotella to be precise, rightly considered the forerunners of this scene. In fact, it was around 1958–1959 that Baj and Rotella abandoned their previous careers (which might exist generically defined as belonging to a non-representational genre, despite existence thoroughly post-Dadaist), to catapult themselves into a new globe of images, and the reflections on them, which was springing upwards all effectually them. Rotella's torn posters showed an always more figurative taste, oftentimes explicitly and deliberately referring to the great icons of the times. Baj'south compositions were steeped in gimmicky kitsch, which turned out to be a "gold mine" of images and the stimulus for an unabridged generation of artists.

The novelty came from the new visual panorama, both within "domestic walls" and out-of-doors. Cars, road signs, television, all the "new earth", everything tin belong to the world of art, which itself is new. In this respect, Italian pop art takes the same ideological path as that of the international scene. The only thing that changes is the iconography and, in some cases, the presence of a more critical attitude toward information technology. Even in this example, the prototypes can be traced dorsum to the works of Rotella and Baj, both far from neutral in their relationship with guild. Nevertheless this is not an sectional element; there is a long line of artists, including Gianni Ruffi, Roberto Barni, Silvio Pasotti, Umberto Bignardi, and Claudio Cintoli, who take on reality every bit a toy, as a great pool of imagery from which to draw material with disenchantment and frivolity, questioning the traditional linguistic function models with a renewed spirit of "let me have fun" à la Aldo Palazzeschi.[58]

Belgium [edit]

In Belgium, pop art was represented to some extent by Paul Van Hoeydonck, whose sculpture Fallen Astronaut was left on the Moon during one of the Apollo missions, as well equally by other notable pop artists. Internationally recognized artists such as Marcel Broodthaers ( 'vous êtes doll? "), Evelyne Axell and Panamarenko are indebted to the popular art movement; Broodthaers'southward groovy influence was George Segal. Another well-known artist, Roger Raveel, mounted a birdcage with a existent live pigeon in 1 of his paintings. By the end of the 1960s and early 1970s, pop art references disappeared from the work of some of these artists when they started to adopt a more critical attitude towards America considering of the Vietnam War'southward increasingly gruesome character. Panamarenko, however, has retained the irony inherent in the pop art movement up to the nowadays 24-hour interval. Evelyne Axell from Namur was a prolific pop-artist in the 1964–1972 period. Axell was one of the first female pop artists, had been mentored past Magritte and her best-known painting is Ice Cream.[59]

Netherlands [edit]

While there was no formal popular fine art movement in holland, there were a group of artists that spent fourth dimension in New York during the early years of popular fine art, and drew inspiration from the international pop art motility. Representatives of Dutch pop art include Daan van Golden, Gustave Asselbergs, Jacques Frenken, January Cremer, Wim T. Schippers, and Woody van Amen. They opposed the Dutch petit bourgeois mentality by creating humorous works with a serious undertone. Examples of this nature include Sex O'Clock, by Woody van Amen, and Crucifix / Target, past Jacques Frenken.[sixty]

Russia [edit]

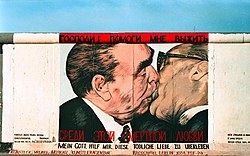

Russia was a little tardily to become part of the popular art move, and some of the artwork that resembles pop art only surfaced around the early 1970s, when Russian federation was a communist country and bold artistic statements were closely monitored. Russia's own version of pop art was Soviet-themed and was referred to as Sots Art. After 1991, the Communist Party lost its ability, and with it came a liberty to express. Pop art in Russia took on some other form, epitomised by Dmitri Vrubel with his painting titled My God, Help Me to Survive This Deadly Dearest in 1990. Information technology might be argued that the Soviet posters made in the 1950s to promote the wealth of the nation were in itself a class of pop art.[61]

Notable artists [edit]

- Billy Apple tree (1935-2021)

- Evelyne Axell (1935–1972)

- Sir Peter Blake (born 1932)

- Derek Boshier (born 1937)

- Pauline Boty (1938–1966)

- Patrick Caulfield (1936–2005)

- Allan D'Arcangelo (1930–1998)

- Jim Dine (born 1935)

- Burhan Dogancay (1929–2013)

- Rosalyn Drexler (born 1926)

- Robert Dowd (1936–1996)

- Ken Elias (born 1944)

- Erró (born 1932)

- Marisol Escobar (1930–2016)

- James Gill (born 1934)

- Dorothy Grebenak (1913-1990)

- Red Grooms (born 1937)

- Richard Hamilton (1922–2011)

- Keith Haring (1958–1990)

- Jann Haworth (born 1942)

- David Hockney (built-in 1937)

- Dorothy Iannone (built-in 1933)

- Robert Indiana (1928–2018)

- Jasper Johns (born 1930)

- Ray Johnson (1927-1995)

- Allen Jones (born 1937)

- Alex Katz (born 1927)

- Corita Kent (1918–1986)

- Konrad Klapheck (born 1935)

- Kiki Kogelnik (1935–1997)

- Nicholas Krushenick (1929–1999)

- Yayoi Kusama (born 1929)

- Gerald Laing (1936–2011)

- Roy Lichtenstein (1923–1997)

- Richard Lindner (1901–1978)

- John McHale (1922–1978)

- Peter Max (born 1937)

- Marta Minujin (born 1943)

- Claes Oldenburg (born 1929)

- Julian Opie (built-in 1958)

- Eduardo Paolozzi (1924–2005)

- Peter Phillips (born 1939)

- Sigmar Polke (1941–2010)

- Hariton Pushwagner (1940–2018)

- Mel Ramos (1935–2018)

- Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008)

- Larry Rivers (1923–2002)

- James Rizzi (1950–2011)

- James Rosenquist (1933–2017)

- Niki de Saint Phalle (1930–2002)

- Peter Saul (built-in 1934)

- George Segal (1924–2000)

- Colin Self (born 1941)

- Marjorie Strider (1931–2014)

- Elaine Sturtevant (1924-2014)

- Wayne Thiebaud (born 1920)

- Joe Tilson (built-in 1928)

- Andy Warhol (1928–1987)

- Idelle Weber (1932–2020)

- John Wesley (built-in 1928)

- Tom Wesselmann (1931–2004)

See also [edit]

- Art pop

- Chicago Imagists

- Ferus Gallery

- Sidney Janis

- Leo Castelli

- Green Gallery

- New Painting of Common Objects

- Figuration Libre (art movement)

- Lowbrow (fine art movement)

- Nouveau réalisme

- Neo-popular

- Op art

- Plop art

- Retro fine art

- Superflat

- SoFlo Superflat

References [edit]

- ^ Popular Art: A Cursory History, MoMA Learning

- ^ a b c d e Livingstone, M., Pop Art: A Standing History, New York: Harry Northward. Abrams, Inc., 1990

- ^ a b c de la Croix, H.; Tansey, R., Gardner's Art Through the Ages, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc., 1980.

- ^ a b c d due east f Piper, David. The Illustrated History of Art, ISBN 0-7537-0179-0, p486-487.

- ^ Harrison, Sylvia (2001-08-27). Pop Fine art and the Origins of Post-Modernism. Cambridge University Printing.

- ^ a b c d Gopnik, A.; Varnedoe, K., High & Low: Modern Art & Popular Culture, New York: The Museum of Mod Fine art, 1990

- ^ "History, Travel, Arts, Scientific discipline, People, Places | Smithsonian". Smithsonianmag.com . Retrieved 2015-12-30 .

- ^ "Modern Beloved". The New Yorker. 2007-08-06. Retrieved 2015-12-30 .

- ^ Wayne Craven, American Art: History and . p.464.

- ^ a b c d due east f g Arnason, H., History of Modernistic Art: Painting, Sculpture, Architecture, New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. 1968.

- ^ "'I was a Rich Man's Plaything', Sir Eduardo Paolozzi". Tate. 2015-12-10. Retrieved 2015-12-30 .

- ^ "John McHale". Warholstars.org . Retrieved 2015-12-30 .

- ^ "Pop fine art", A Dictionary of Twentieth-Century Art, Ian Chilvers. Oxford University Press, 1998.

- ^ "Popular fine art", The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms, Michael Clarke, Oxford University Printing, 2001.

- ^ Alison and Peter Smithson, "Merely Today We Collect Ads", reprinted on page 54 in Modern Dreams The Ascension and Fall of Pop, published past ICA and MIT, ISBN 0-262-73081-2

- ^ Lawrence Alloway, "The Arts and the Mass Media," Architectural Blueprint & Structure, February 1958.

- ^ a b Klaus Honnef, Pop Art, Taschen, 2004, p. 6, ISBN 3822822183

- ^ a b Barton, Christina (2010). Billy Apple: British and American Works 1960–69. London: The Mayor Gallery. pp. 11–21. ISBN978-0-9558367-iii-2.

- ^ a b c d Scherman, Tony. "When Popular Turned the Art World Upside Down." American Heritage 52.1 (February 2001), 68.

- ^ Geldzahler, Henry in Pop Fine art: 1955–1970 catalogue, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1985

- ^ Lippard, Lucy in Ray Johnson: Correspondences catalogue, Wexner Center/Whitney Museum, 2000

- ^ Bloch, Mark. "An Illustrated Introduction to Ray Johnson 1927-1995", 1995

- ^ Author unknown. "(Table of contents, Untitled annotation near comprehend.)", Art News, vol. 56, no. 9, January 1958

- ^ Rauschenberg, Robert; Miller, Dorothy C. (1959). Sixteen Americans [exhibition]. New York: Museum of Modern Fine art. p. 58. ISBN 978-0029156704. OCLC 748990996. "Painting relates to both fine art and life. Neither can exist made. (I try to deed in that gap between the two.)"

- ^ "Art: Pop Fine art – Cult of the Commonplace". Fourth dimension. 1963-05-03. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 2020-07-07 .

Robert Rauschenberg, 37, remembers an art instructor who 'taught me to think, "Why non?"' Since Rauschenberg is considered to be a pioneer in popular art, this is probably where the movement went off on its particular tangent. Why not make art out of old newspapers, bits of clothing, Coke bottles, books, skates, clocks?

- ^ Sandler, Irving H. The New York School: The Painters and Sculptors of the Fifties, New York: Harper & Row, 1978. ISBN 0-06-438505-1 pp. 174–195, Rauschenberg and Johns; pp. 103–111, Rivers and the gestural realists.

- ^ Rosenthal, Nan (October 2004). "Jasper Johns (born 1930) In Heilbrunn Timeline of Fine art History". The Metropolitan Museum of Art . Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- ^ Robert Rosenblum, "Jasper Johns" Art International (September 1960): 75.

- ^ Hapgood, Susan, Neo-Dada: Redefining Art, 1958–62. New York: Universe Books, 1994.

- ^ Hendrickson, Janis (1988). Roy Lichtenstein. Cologne, Germany: Benedikt Taschen. p. 31. ISBN3-8228-0281-half dozen.

- ^ Kimmelman, Michael (September thirty, 1997). "Roy Lichtenstein, Pop Master, Dies at 73". New York Times . Retrieved Nov 12, 2007.

- ^ Michelson, Annette, Buchloh, B. H. D. (eds) Andy Warhol (October Files), MIT Press, 2001.

- ^ Warhol, Andy. The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, from A to B and back again. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1975

- ^ "The Collection". MoMA.org . Retrieved 2015-12-30 .

- ^ "The Great American Pop Art Store: Multiples of the Sixties". Tfaoi.com . Retrieved 2015-12-thirty .

- ^ Diggory (2013).

- ^ a b Kristine McKenna (July 2, 1995), When Bigger Is Amend: Claes Oldenburg has spent the by 35 years blowing up and redefining everyday objects, all in the name of getting art off its pedestal Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Reva Wolf (1997-eleven-24). Andy Warhol, Poetry, and Gossip in the 1960s. p. 83. ISBN9780226904931 . Retrieved 2015-12-30 .

- ^ "Museum History » Norton Simon Museum". Nortonsimon.org . Retrieved 2015-12-30 .

- ^ Six painters and the object. Lawrence Alloway [curator, conceived and prepared this exhibition and the catalogue] (Figurer file). 2009-07-24. OCLC 360205683.

- ^ Gayford, Martin (2002-12-19). "Notwithstanding life at the check-out". The Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group Ltd. Archived from the original on 2022-01-eleven. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ^ Pop Artists: Andy Warhol, Pop Art, Roy Lichtenstein, Jasper Johns, Peter Max, Erró, David Hockney, Wally Hedrick, Michael Leavitt (May 20, 2010) Reprinted: 2010, General Books, Memphis, Tennessee, U.s.a., ISBN 978-ane-155-48349-8, ISBN 1-155-48349-ix.

- ^ Jim Edwards, William Emboden, David McCarthy: Uncommonplaces: The Art of James Francis Gill, 2005, p.54

- ^ Karl Ruhrberg, Ingo F. Walther, Art of the 20th Century, Taschen, 2000, p. 518. ISBN 3-8228-5907-nine

- ^ a b Kerstin Stremmel, Realism, Taschen, 2004, p. 13. ISBN 3-8228-2942-0

- ^ Rosemary M. O'Neill, Art and Visual Culture on the French Riviera, 1956–1971: The Ecole de Nice, Ashgate, 2012, p. 93.

- ^ lx/90. Trente ans de Nouveau Réalisme, La Différence, 1990, p. 76

- ^ "Op + Pop". christchurchartgallery.org.nz . Retrieved 2021-07-22 .

- ^ "Dick Frizzell - Overview". The Central . Retrieved 2021-07-22 .

- ^ "Loading... | Collections Online - Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa". collections.tepapa.govt.nz . Retrieved 2021-07-22 .

- ^ "Loading... | Collections Online - Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa". collections.tepapa.govt.nz . Retrieved 2021-07-22 .

- ^ "ARTSPACE - Billy Apple". 2013-02-09. Archived from the original on 2013-02-09. Retrieved 2021-07-29 .

- ^ Eskola, Jack (2015). Harue Koga: David Bowie of the Early 20th Century Japanese Fine art Advanced. Kindle, due east-book.

- ^ Bloch, Mark. The Brooklyn Rail. "Gutai: 1953 –1959", June 2018.

- ^ "Yayoi Kusama interview – Yayoi Kusama exhibition". Timeout.com. 2013-01-30. Retrieved 2015-12-30 .

- ^ [1] Archived Nov 1, 2012, at the Wayback Motorcar

- ^ "Tadanori Yokoo : ADC • Global Awards & Club". Adcglobal.org. 1936-06-27. Retrieved 2015-12-30 .

- ^ "Pop Art Italian republic 1958–1968 — Galleria Civica". Comune.modena.it . Retrieved 2015-12-30 .

- ^ "Philadelphia Museum of Art Wins Fight with Facebook over Racy Pop Art Painting". artnet.com. xi February 2016. Retrieved 2020-01-17 .

- ^ "Dutch Pop Art & The Sixties – Weg met de vertrutting!". 8weekly.nl. 28 July 2005. Retrieved 2015-12-30 .

- ^ [ii] Archived June 7, 2013, at the Wayback Auto

Further reading [edit]

- Bloch, Mark. The Brooklyn Rail. "Gutai: 1953 –1959", June 2018.

- Diggory, Terence (2013) Encyclopedia of the New York School Poets (Facts on File Library of American Literature). ISBN 978-1-4381-4066-seven

- Francis, Marking and Foster, Hal (2010) Pop. London and New York: Phaidon.

- Haskell, Barbara (1984) BLAM! The Explosion of Pop, Minimalism and Performance 1958–1964. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. in association with the Whitney Museum of American Art.

- Lifshitz, Mikhail, The Crunch of Ugliness: From Cubism to Popular-Art. Translated and with an Introduction past David Riff. Leiden: BRILL, 2018 (originally published in Russian by Iskusstvo, 1968).

- Lippard, Lucy R. (1966) Pop Art, with contributions by Lawrence Alloway, Nancy Marmer, Nicolas Calas, Frederick A. Praeger, New York.

- Selz, Peter (moderator); Ashton, Dore; Geldzahler, Henry; Kramer, Hilton; Kunitz, Stanley and Steinberg, Leo (April 1963) "A symposium on Popular Fine art" Arts Mag, pp. 36–45. Transcript of symposium held at the Museum of Mod Art on Dec thirteen, 1962.

External links [edit]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pop art. |

| | Wikiquote has quotations related to: Pop fine art |

- Pop Art: A Cursory History, MoMA Learning

- Popular Fine art in Modern and Contemporary Art, The Met

- Brooklyn Museum Exhibitions: Seductive Subversion: Women Pop Artists, 1958–1968, Oct. 2010-Jan. 2011

- Brooklyn Museum, Wiki/Popular (Women Popular Artists)

- Tate Glossary term for Pop art

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pop_art

0 Response to "What Distinguishes Adbusters From Earlier Movements Like Pop Art and Fluxus?"

Publicar un comentario